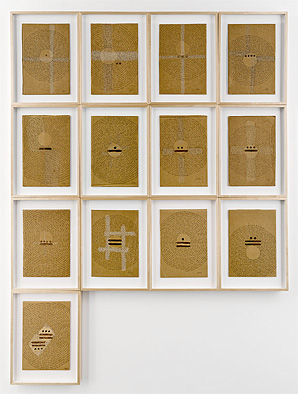

![Presence, 2009-2010<br />Library: work by Melik Ohanian [detail]](13.jpg)

![Presence, 2009-2010<br />Library: work by Melik Ohanian [detail]](14.jpg)

Presence

Nov 5, 2009 – Jul 23, 2010

The current installation of The Rachofsky Collection grew out of the recent acquisition of a rather ephemeral work by a young New York-based artist, Gedi Sibony, consisting of a carpet, a nearly invisible yet somehow architectural plastic construction, and a light, and the concurrent desire to present two large-scale works, one by a central artist in the collection, Giulio Paolini, and the other by a relatively unknown French artist, Melik Ohanian. Presence brings together a diverse range of paintings, sculptures, videos, and installations of slight and often fragmentary materiality, whose perceptual and psychological presence is greater than their physical form. Of course one could say that about most works of art—at least most lasting ones—but here in particular what is seen is a trigger for a far greater field of experience and thought.

And so, throughout the installation, one finds art made of fragments of things, flickers of light, mirrors, reflections, suggestions of things obscured or hidden, parts of bodies, of selves, things of tenuous balance, nuances of the textures of monochrome. Where there are images, they are often difficult to fully apprehend (Brauntuch, Crewdson); the figure, when represented, is never whole (Kelly, Mapplethorpe). When the artist does portray something "whole," it is as ephemeral or immeasurable as Robert Irwin's historical acrylic disk of 1968-69, itself a portrait of the limitlessness of perception, or it has the elusive presence of Mona Hatoum's +and-, consisting of a serrated metal blade that simultaneously marks and erases its presence with the gentle rotation of a circle in a proverbial container of sand.

The current installation does indeed ask the question, What does it mean to be present? Perhaps this is no more concretely examined than in David Altmejd's huge sculpture of a figure covered in mirrors, an absent presence whose massive corporeality seems to dissolve into fractured reflections of all that is around it. This notion of the surface of the artwork as a portal to its own disappearance is established in Richard Artschwager's historical work of 1964, Swivel, in which the very notions of "positive" and "negative" space are challenged and reversed, with the object in insubstantive white and its void suggested by a solid of black. Félix Gonzalez-Torres' photographic work, an anti-monumental monument, portrays a man as a kind of abstraction by words etched into architecture that identify his actions rather than, as in traditional portraiture, by his physical appearance.

The presence of the artist, or rather the artist's disappearance, is evident everywhere, whether in the elimination of the painter's hand or in the overriding absence of the figure. In another Paolini work, from 1964, which can be viewed as a kind of self-portrait, the artist, and his work, have been reduced to the tools of the trade, paintbrushes atop a sheet of plywood. In a much more recent work by Rirkrit Tiravanija, made of the artist's unfolded passports, dense with visas from dozens of places the artist has visited, the world has become the artist's studio, and his life his art. Even when the artist portrays himself, as in Bruce Nauman's Setting a Good Corner (Allegory & Metaphor), he is no longer an artist at all, but a worker living his life building a gate on his ranch.

Presence includes works that span six decades. And while they are displayed in a deliberately anti-historical arrangement, this installation aims to examine evolving conceptions of self in the period following World War II until today. While artists from the Abstract Expressionists in the 1950s to the Neo-Expressionists in the 80s have defined the mainstream view of expressions of self in the postwar era, the focus of this installation, and in many ways of The Rachofsky Collection in general, is on less tangible examinations of identity, of often uneasily shifting conceptions of the boundaries of the self that also parallel the unfixed nature of perception. This theme is established in the earliest work in Presence, Lucio Fontana's Concetto spaziale of 1950-53, which examines the artist's lifelong investigation of the space beyond the canvas, or beyond the body. In a related way and at a similar time (1954), in a work produced by peeling a mass of posters off a building façade and displaying the underside, Mimmo Rotella looks at our world and our place within it even when that place may seem thoroughly absent. This unfixed and therefore often unsettling sense of the figure, or of oneself in the world, speaks of a contemporary melancholia that from the work of Paolini in the 60s to Altmejd today can be seen as an underlying theme of the art of our time and of this installation in particular.

The fluidity of the boundary between ourselves and our surrounds, just like that between positive and negative space that is abundant throughout Presence, also speaks of the breakdown of the theoretical divide between representation and abstraction that has been one of the central principles of Modern Art. Indeed, if one of the central trajectories of Modern Art has been the increasingly articulated and reduced assertion of the artwork as a real object in real space, then Félix Gonzalez-Torres' sculpture made of candy throws those distinctions and their values on their side, using the pure forms of Minimalism as a vehicle for a kind of portraiture, as a way of reintroducing human presence into what had been the sacrosanct (and pure) language of abstraction, of Modern Art. This is both an esthetic statement and a political act, a gentle storming of the gates that seems appropriate enough to this age of psychological fragmentation, fractal imaging, and a reconfiguration of the world map, where, as one sees throughout the current installation, the part can be a whole and what is present is just as potently marked by its absence.

Allan Schwartzman

Director of The Rachofsky Collection

November 2009

Nov 5, 2009 – Jul 23, 2010

The current installation of The Rachofsky Collection grew out of the recent acquisition of a rather ephemeral work by a young New York-based artist, Gedi Sibony, consisting of a carpet, a nearly invisible yet somehow architectural plastic construction, and a light, and the concurrent desire to present two large-scale works, one by a central artist in the collection, Giulio Paolini, and the other by a relatively unknown French artist, Melik Ohanian. Presence brings together a diverse range of paintings, sculptures, videos, and installations of slight and often fragmentary materiality, whose perceptual and psychological presence is greater than their physical form. Of course one could say that about most works of art—at least most lasting ones—but here in particular what is seen is a trigger for a far greater field of experience and thought.

And so, throughout the installation, one finds art made of fragments of things, flickers of light, mirrors, reflections, suggestions of things obscured or hidden, parts of bodies, of selves, things of tenuous balance, nuances of the textures of monochrome. Where there are images, they are often difficult to fully apprehend (Brauntuch, Crewdson); the figure, when represented, is never whole (Kelly, Mapplethorpe). When the artist does portray something "whole," it is as ephemeral or immeasurable as Robert Irwin's historical acrylic disk of 1968-69, itself a portrait of the limitlessness of perception, or it has the elusive presence of Mona Hatoum's +and-, consisting of a serrated metal blade that simultaneously marks and erases its presence with the gentle rotation of a circle in a proverbial container of sand.

The current installation does indeed ask the question, What does it mean to be present? Perhaps this is no more concretely examined than in David Altmejd's huge sculpture of a figure covered in mirrors, an absent presence whose massive corporeality seems to dissolve into fractured reflections of all that is around it. This notion of the surface of the artwork as a portal to its own disappearance is established in Richard Artschwager's historical work of 1964, Swivel, in which the very notions of "positive" and "negative" space are challenged and reversed, with the object in insubstantive white and its void suggested by a solid of black. Félix Gonzalez-Torres' photographic work, an anti-monumental monument, portrays a man as a kind of abstraction by words etched into architecture that identify his actions rather than, as in traditional portraiture, by his physical appearance.

The presence of the artist, or rather the artist's disappearance, is evident everywhere, whether in the elimination of the painter's hand or in the overriding absence of the figure. In another Paolini work, from 1964, which can be viewed as a kind of self-portrait, the artist, and his work, have been reduced to the tools of the trade, paintbrushes atop a sheet of plywood. In a much more recent work by Rirkrit Tiravanija, made of the artist's unfolded passports, dense with visas from dozens of places the artist has visited, the world has become the artist's studio, and his life his art. Even when the artist portrays himself, as in Bruce Nauman's Setting a Good Corner (Allegory & Metaphor), he is no longer an artist at all, but a worker living his life building a gate on his ranch.

Presence includes works that span six decades. And while they are displayed in a deliberately anti-historical arrangement, this installation aims to examine evolving conceptions of self in the period following World War II until today. While artists from the Abstract Expressionists in the 1950s to the Neo-Expressionists in the 80s have defined the mainstream view of expressions of self in the postwar era, the focus of this installation, and in many ways of The Rachofsky Collection in general, is on less tangible examinations of identity, of often uneasily shifting conceptions of the boundaries of the self that also parallel the unfixed nature of perception. This theme is established in the earliest work in Presence, Lucio Fontana's Concetto spaziale of 1950-53, which examines the artist's lifelong investigation of the space beyond the canvas, or beyond the body. In a related way and at a similar time (1954), in a work produced by peeling a mass of posters off a building façade and displaying the underside, Mimmo Rotella looks at our world and our place within it even when that place may seem thoroughly absent. This unfixed and therefore often unsettling sense of the figure, or of oneself in the world, speaks of a contemporary melancholia that from the work of Paolini in the 60s to Altmejd today can be seen as an underlying theme of the art of our time and of this installation in particular.

The fluidity of the boundary between ourselves and our surrounds, just like that between positive and negative space that is abundant throughout Presence, also speaks of the breakdown of the theoretical divide between representation and abstraction that has been one of the central principles of Modern Art. Indeed, if one of the central trajectories of Modern Art has been the increasingly articulated and reduced assertion of the artwork as a real object in real space, then Félix Gonzalez-Torres' sculpture made of candy throws those distinctions and their values on their side, using the pure forms of Minimalism as a vehicle for a kind of portraiture, as a way of reintroducing human presence into what had been the sacrosanct (and pure) language of abstraction, of Modern Art. This is both an esthetic statement and a political act, a gentle storming of the gates that seems appropriate enough to this age of psychological fragmentation, fractal imaging, and a reconfiguration of the world map, where, as one sees throughout the current installation, the part can be a whole and what is present is just as potently marked by its absence.

Allan Schwartzman

Director of The Rachofsky Collection

November 2009